Milton descended into Blake's left foot! (Davis, 105). Blake wrote of the psychological dimensions of the fall of Adam that he allegorized to the thought of Boehme. Opinions beyond recourse made those who knew him call him mad, which is given substance in records of his conversation in Ellis and Yeats in The Works of William Blake, I, the memoirs. But if there is much impetuous expression in Blake he has to be taken seriously for the body of backward engravings in a small hand he made for public sale. This is compulsion beyond. If some many of his scurrilous works had not been burned by this executor the situation would be worse.

Plain as any Mennonite, Blake took his denomination of being seriously, would be labeled a dissenter and sectarian if any group fit. Efforts to degrade him into known categories and paradigms past or present don't work, . He is no more a tantracist than a mescaline user.To think he speaks for any other party is to reduce him to the commonplace as is done when Coleridge's pipe is celebrated more than his mountain climb (see Macfarlane, Mountains of the Mind, 81-84).

Lately they try to divorce Blake's wife, who was especially devoted to him, from him, in effort to put them asunder and have Blake for themselves.Critics need pepper to blind the eye so no one can see the fraud they perpetuate. This peppery criticism makes for instant reputation. Another problem for all this, is Blake is a Christian.

There has been a revolution of the tools of thought and access to Blake's life. Thus the incomprehensibility of books about him begins to pass. Most of these are written in the complex sentences of scholars in apposition. Now, if you can sit down in a chair before the Princeton Editions or the Blake Archives and look at the pictures. You pretty quick understand Blake's religion is the simple, complicated, ecstatic, nonconformist, charismatic, prophetic, biblical kind. Art is his gospel fruit and he turns theosophy on its head. He says God is man, not man is God.

Read in context with the contemporary George Whitfield he agrees with nothing and everything. Critics once tried to enter his life through his work, but it is easy to enter his work through his life. In the end if he says some mad thing, which he will do, but his life proves his work serious, discipline proves him sound. In his own time his "pleasing, mild disposition" was said to be the only thing that kept him from being put in an institution. Mad poets, now celebrated, threatened conformity.

Read in context with the contemporary George Whitfield he agrees with nothing and everything. Critics once tried to enter his life through his work, but it is easy to enter his work through his life. In the end if he says some mad thing, which he will do, but his life proves his work serious, discipline proves him sound. In his own time his "pleasing, mild disposition" was said to be the only thing that kept him from being put in an institution. Mad poets, now celebrated, threatened conformity. He is still being made over. His mind must be ruled to save him from himself! Such notions always overwhelm martyr and visionary. Monastics, Moravians, Mennonites, Quakers, Dunkers are ready to sacrifice the outer world for the inner.

Blake Is A Christian

Blake's life confronts the inner/outer world. From Pilgrim's Progress, melancholy poems about The Grave, Michelangelo's notion of creation, Milton's ditto and on, it's folly not to see Blake in the center of this context, with his own take on every Biblical idea of outer versus inner, world versus spirit. "Free yourself from the world," says also Chuang Tzu.The experience of the spirit world, especially the biblical part of it libeled as hopeless fundamentalism in prophecies of "end times" is not what it seems. One sentence from Yeats is better than whole books. Even spiritualized as Yeats is when he says that for Blake "Christ was his symbolic name for the imagination" (xvii), this partial truth is better than whole lies from the moths of instruction. So when Yeats seems to have his way with finding and losing his life, he makes a greater statement. He says that Blake "came to look upon poetry and art as a language for the utterance of conceptions, which, however beautiful, were none the less thought out more for their visionary truth than for their beauty. The change made him a greater poet and a greater artist; for 'He that findeth his life shall lose it, and he that loseth his life for My sake shall find it'" (xvii). Surveyed with an open eye only the hugest figures have celebrated that Name above every name that Yeats names.

Blake's life confronts the inner/outer world. From Pilgrim's Progress, melancholy poems about The Grave, Michelangelo's notion of creation, Milton's ditto and on, it's folly not to see Blake in the center of this context, with his own take on every Biblical idea of outer versus inner, world versus spirit. "Free yourself from the world," says also Chuang Tzu.The experience of the spirit world, especially the biblical part of it libeled as hopeless fundamentalism in prophecies of "end times" is not what it seems. One sentence from Yeats is better than whole books. Even spiritualized as Yeats is when he says that for Blake "Christ was his symbolic name for the imagination" (xvii), this partial truth is better than whole lies from the moths of instruction. So when Yeats seems to have his way with finding and losing his life, he makes a greater statement. He says that Blake "came to look upon poetry and art as a language for the utterance of conceptions, which, however beautiful, were none the less thought out more for their visionary truth than for their beauty. The change made him a greater poet and a greater artist; for 'He that findeth his life shall lose it, and he that loseth his life for My sake shall find it'" (xvii). Surveyed with an open eye only the hugest figures have celebrated that Name above every name that Yeats names.

Myrrh

Blake as a Christian is a stumbling block, but so is his marriage to and love of Kate. He would understand that myrrh drips from the handles of the lock. Who among the poets had a wife who sustained a lifelong relation of devotion, who not only took care and gave life and continuity to the poet, but who did his work, his printing and who was his sole model and consort? This dream eluded Yeats. Blake and Catharine used to take 40 mile walks together in the countryside. Aesthetes say Catharine got old and Blake was threadbare and dirty. He was a printer. They lived spare, were not thought to be the people they were. Not worldly at all. Is there one other who had his riches? Emily Dickinson. Kate was his sole model and consort! She was beautiful. Whatever you think Blake was about it hugely concerned the sensual, the sexual, the female in the same way this preoccupied Joyce. Whatever it is we're after in the life of Blake takes to task in us our essential eroticism and identity. Yeats deeply desired in a companion what Blake had, so he would know its value when he says that with Kate, Blake had a "love that knew no limit and a friendship that knew no flaw" (xx).

Blake as a Christian is a stumbling block, but so is his marriage to and love of Kate. He would understand that myrrh drips from the handles of the lock. Who among the poets had a wife who sustained a lifelong relation of devotion, who not only took care and gave life and continuity to the poet, but who did his work, his printing and who was his sole model and consort? This dream eluded Yeats. Blake and Catharine used to take 40 mile walks together in the countryside. Aesthetes say Catharine got old and Blake was threadbare and dirty. He was a printer. They lived spare, were not thought to be the people they were. Not worldly at all. Is there one other who had his riches? Emily Dickinson. Kate was his sole model and consort! She was beautiful. Whatever you think Blake was about it hugely concerned the sensual, the sexual, the female in the same way this preoccupied Joyce. Whatever it is we're after in the life of Blake takes to task in us our essential eroticism and identity. Yeats deeply desired in a companion what Blake had, so he would know its value when he says that with Kate, Blake had a "love that knew no limit and a friendship that knew no flaw" (xx).

Blake Is A Christian

Blake's life confronts the inner/outer world. From Pilgrim's Progress, melancholy poems about The Grave, Michelangelo's notion of creation, Milton's ditto and on, it's folly not to see Blake in the center of this context, with his own take on every Biblical idea of outer versus inner, world versus spirit. "Free yourself from the world," says also Chuang Tzu.The experience of the spirit world, especially the biblical part of it libeled as hopeless fundamentalism in prophecies of "end times" is not what it seems. One sentence from Yeats is better than whole books. Even spiritualized as Yeats is when he says that for Blake "Christ was his symbolic name for the imagination" (xvii), this partial truth is better than whole lies from the moths of instruction. So when Yeats seems to have his way with finding and losing his life, he makes a greater statement. He says that Blake "came to look upon poetry and art as a language for the utterance of conceptions, which, however beautiful, were none the less thought out more for their visionary truth than for their beauty. The change made him a greater poet and a greater artist; for 'He that findeth his life shall lose it, and he that loseth his life for My sake shall find it'" (xvii). Surveyed with an open eye only the hugest figures have celebrated that Name above every name that Yeats names.

Blake's life confronts the inner/outer world. From Pilgrim's Progress, melancholy poems about The Grave, Michelangelo's notion of creation, Milton's ditto and on, it's folly not to see Blake in the center of this context, with his own take on every Biblical idea of outer versus inner, world versus spirit. "Free yourself from the world," says also Chuang Tzu.The experience of the spirit world, especially the biblical part of it libeled as hopeless fundamentalism in prophecies of "end times" is not what it seems. One sentence from Yeats is better than whole books. Even spiritualized as Yeats is when he says that for Blake "Christ was his symbolic name for the imagination" (xvii), this partial truth is better than whole lies from the moths of instruction. So when Yeats seems to have his way with finding and losing his life, he makes a greater statement. He says that Blake "came to look upon poetry and art as a language for the utterance of conceptions, which, however beautiful, were none the less thought out more for their visionary truth than for their beauty. The change made him a greater poet and a greater artist; for 'He that findeth his life shall lose it, and he that loseth his life for My sake shall find it'" (xvii). Surveyed with an open eye only the hugest figures have celebrated that Name above every name that Yeats names.Myrrh

Blake as a Christian is a stumbling block, but so is his marriage to and love of Kate. He would understand that myrrh drips from the handles of the lock. Who among the poets had a wife who sustained a lifelong relation of devotion, who not only took care and gave life and continuity to the poet, but who did his work, his printing and who was his sole model and consort? This dream eluded Yeats. Blake and Catharine used to take 40 mile walks together in the countryside. Aesthetes say Catharine got old and Blake was threadbare and dirty. He was a printer. They lived spare, were not thought to be the people they were. Not worldly at all. Is there one other who had his riches? Emily Dickinson. Kate was his sole model and consort! She was beautiful. Whatever you think Blake was about it hugely concerned the sensual, the sexual, the female in the same way this preoccupied Joyce. Whatever it is we're after in the life of Blake takes to task in us our essential eroticism and identity. Yeats deeply desired in a companion what Blake had, so he would know its value when he says that with Kate, Blake had a "love that knew no limit and a friendship that knew no flaw" (xx).

Blake as a Christian is a stumbling block, but so is his marriage to and love of Kate. He would understand that myrrh drips from the handles of the lock. Who among the poets had a wife who sustained a lifelong relation of devotion, who not only took care and gave life and continuity to the poet, but who did his work, his printing and who was his sole model and consort? This dream eluded Yeats. Blake and Catharine used to take 40 mile walks together in the countryside. Aesthetes say Catharine got old and Blake was threadbare and dirty. He was a printer. They lived spare, were not thought to be the people they were. Not worldly at all. Is there one other who had his riches? Emily Dickinson. Kate was his sole model and consort! She was beautiful. Whatever you think Blake was about it hugely concerned the sensual, the sexual, the female in the same way this preoccupied Joyce. Whatever it is we're after in the life of Blake takes to task in us our essential eroticism and identity. Yeats deeply desired in a companion what Blake had, so he would know its value when he says that with Kate, Blake had a "love that knew no limit and a friendship that knew no flaw" (xx).

2.

Great oddities occur after Blake is dead. Frederick Tatham disposed of his poetic estate, burned piles of things, but everybody else has had their day with the objectionable. Blake himself burned a lot of dross. The same flame draws the Many Moth (critics). In some ways Blake was better off in obscurity. Moths obscure the light of his work with tantric, alchemic occultisms. The sensational critical environment is so extreme that Yeats hits a kind of center when he says that Blake displays a profound sanity because he never "pronounced himself to be chosen and set apart alone among men" (xii), rightly seeing megalomania as a common modern disease The problem with Tatham's taste is that he was a convinced Irvingite, given to all those abuses of the spiritual, and as biographer Bentley says, he was convinced by the sect that Blake's inspiration was infernal. Young C.S. Lewis, "shown up a long stairway [of Yeats] lined with rather wicked pictures by Blake--all devils and monsters" (Letters. ed, by W. H. Lewis. Geoffrey Bles 1966, 57). So Tatham burned everything he did not later sell of "blocks, plates, drawings and MMS (Bentley Jr., 446). The rumors of what this estate consisted of are better left unseen because with Blake whatever shards torn from the carcass are most often magnified to the loss of the whole, whether it be his so-called empire or presumed philosophies filtered through a thousand critics who pull him asunder.

Munich in the Head

No matter what the parties and parochialisms, all have had their Blake, the latest being tantric sex, prolonging ecstasy forced upon Blake by way of Count Zinzendorf, making Blake's relation with his wife over into what only those alleging authors can know from their own, as Marsha Keith Schuchard has confessed. So if we cannot know what and why Mrs. Blake cried, since it has been done to Schuchard, namely all of it was not done to Kate. Blake lived in perpetual ecstasy. How do we know? Get married yourself and find out. The train of logic is that Blake read Swedenborg and Swedenborg emerged from Count Zinzendorf''s cult so dictated to, but not the way Milton and Blake were dictated to. The small can never comprehend the great, the self muse of the front brain cannot comprehend the Holy Spirit. As to Zinzendorf, it was known long before in Pennsylvania who he was when he decided that all the sects, Mennonites, Reformed could fit into the great arms of his faith. The Count was willing. Read Muhlenberg on Zinzendorf before concluding.

Tantric alchemy and tantricism together remind of John Dee and Edward Kelley, proving how much the spirit world lust wants to get in your pants. Whether to suppress orgasm and recycle eternal energy, maybe never die, the spirit told Kelley to tell Dee to send Jane, Dee's wife, to his bed. Count Zinzendorf wanted to be there too. If grad students and profs take the Munich from the side of their head, their delusion of wisdom, they dress up Blake and Kate in doll clothes, make them Ken and Barbie so they will reflect the very reality those students and profs know. Blake is a Christian not in words but in the life. Unless you live it the words mean nothing.

3.

3. Pray

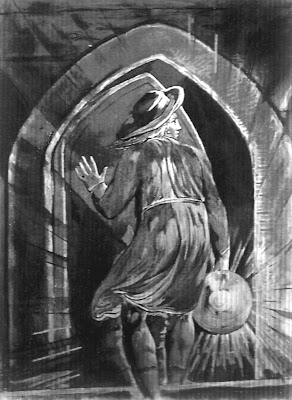

We can be healthily skeptical of people who greet one another and ask, "is that Michael or Gabriel?" As if they commonly appeared in bookstores. If anybody can be believed that Gabriel sat for his portrait, as Blake is said to have told Thomas Phillips while having his portrait done, Blake might: "he waved his hands; the roof of my study opened; he ascended into heaven; he stood in the sun, and beckoning to me, moved the universe (Davis, 121). Among many monastic devotees of the inner world, Blake is alone. Sake of argument grants that his chief hero, Los the imagination, is tarnished as he enters the doors of perception. It is Blake's psychological allegory of the Fall.

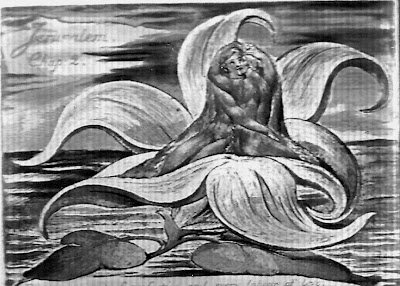

So Blake found a Way Into the Flowering Heart where you can live every day, or just those days when you are not high. Be temporal and eternal.

So Blake found a Way Into the Flowering Heart where you can live every day, or just those days when you are not high. Be temporal and eternal.

Blake turns over the cart, thinks what has been done to the essence of truth is its assassin. Blake turns angels into devils to say that. If there's a hero of literature it's Blake. He takes the top of the head of the reader off partly because his extreme thought sometimes derives from even extremer, say Swedenborg, but mostly because Blake does not suffer fools. Support for many radical views found in his politics and poetics prove Blake a Christian the same way as Edwin Muir, translator of Kafka. After every devotion to Nietzsche and psychological difficulties, terrors of psycho-analysis, which he says stemmed from his fundamentalist upbringing and a forced religious experience when he was 14, he says, "I realized, that quite without knowing it, I was a Christian." (An Autobiography. Seabury, 1968. 168, 247).

Blake forgets to be corrosive when he and his wife kneel and pray to the Holy Spirit for inspiration. (William Blake. A New Kind of Man. Michael Davis. 1977, 155). Imagine what critics do when he reincarnates Milton, as outside the rationalist experience as Milton's insistence that the Holy Ghost dictated Paradise Lost to him each night in entirety, which he told to his daughter the next day. So much of what passes for understanding by critics is amoral black and white. They are the very fundamentalists they themselves should flee. The artistic case has even more contradiction than the general human. To withstand the contradictions of Blake's opposite states without compromising the portrait he gives of himself as a Christian is often too much for critical funds. They must make him fit their idea of rationality and art, which they have been doing anyway everywhere, completely absurd.

Blake forgets to be corrosive when he and his wife kneel and pray to the Holy Spirit for inspiration. (William Blake. A New Kind of Man. Michael Davis. 1977, 155). Imagine what critics do when he reincarnates Milton, as outside the rationalist experience as Milton's insistence that the Holy Ghost dictated Paradise Lost to him each night in entirety, which he told to his daughter the next day. So much of what passes for understanding by critics is amoral black and white. They are the very fundamentalists they themselves should flee. The artistic case has even more contradiction than the general human. To withstand the contradictions of Blake's opposite states without compromising the portrait he gives of himself as a Christian is often too much for critical funds. They must make him fit their idea of rationality and art, which they have been doing anyway everywhere, completely absurd.

Prophet

Talk about straining out a gnat to swallow a camel! A lot of Blake's biography derives from Tatham whose reports give Blake a pietistic tincture, reporting practices of prayer that indicate he is the opposite of a free thinker. The same Tatham burned and disposed much of Blake's literary remains. It did not meet his approval. Just so, critics continue to seek a Blake they can comfortably digest, but his rampant evangelicism is not to their taste. Blake is a prophet in the biblical vein. He says and does things as unprecedented as the biblical prophets.

A comparison for fraktur art and the way into the flowering heart in Blake stems not only from the art, but from the faith. As Stoudt says (Pennsylvania German Folk Art, 24) it is only when a species of disbelief took hold in the minds of the Pennsylvania faithful, what he calls liberalism, that their art failed. And that art under digital magnification continues to amaze, as we hope to show. So what of their faith? There are so many ex-fundamentalists with delicate sensibilities, but good upbringings, that many readers of Blake and Fraktur are impaired by their previous lives. Without naming names of our contemporary literary peers (at least not yet), this case affects Blake, who is celebrated for his "corrosive" art in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell, but only because critics pretend Blake is not a Christian.

What the Redeemed Do

What the Redeemed Do

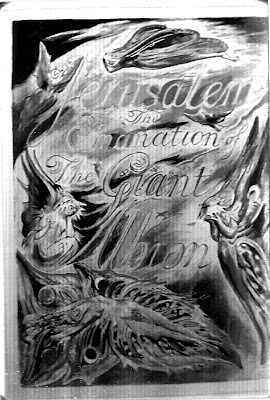

Blake is rather more than merely a Christian in name. He is one in his art, poetry and life, easiest to see in the art maybe, but in his poetry it is more dramatic. Critics gloss over these passages even as they explain them away, as Yeats does in his Introduction (Poems of William Blake), but there it still is, for example in Jerusalem where Blake invites, "I hope the reader will be with me wholly one in Jesus our Lord who is the God and Lord to whom the Ancients look'd and saw his day afar off with trembling & amazement." That alone goes further than allowed by the modern editor. Sorry Blake, "that isn't quite right for us." But Blake published himself and said what he would. Of course the subjects of his art are wholly biblical in every way, Job, notwithstanding the erosion that occurs from disinformation. If it sounds like this is a conspiracy to deny Blake his own faith, it is his critics who have denied their own.

In his personal life the reports of Blake and his wife are supernaturally scandalous, which information comes from Linnell. Of the application of fundamentalist attitudes to the poets however, witness the psychological dissection of Hopkins, who if he were what anthropologists used to call a "salvage" would have his own museum of reconstructions. Here he is a degenerate, there a fascist, any and all things where the good is remade into stereotypical evil that gets young peppery guys published. The essence of the fundamentalist attitude is celebrated "outward ceremony," Wayne Dwyer selling his 20,000 books and moving to Maui to follow the Tao, just what Oprah would like, an easy grasp of the profound. Blake says that the eternal body of man is the imagination and that to be a Christian is to be an artist, a poet/painter/musician/architect, and that that is the only preoccupation of the mind, gained over life and work, not in ease. Then we can know who the Christians are, not that art makes them so, it is just what the redeemed do.

In his personal life the reports of Blake and his wife are supernaturally scandalous, which information comes from Linnell. Of the application of fundamentalist attitudes to the poets however, witness the psychological dissection of Hopkins, who if he were what anthropologists used to call a "salvage" would have his own museum of reconstructions. Here he is a degenerate, there a fascist, any and all things where the good is remade into stereotypical evil that gets young peppery guys published. The essence of the fundamentalist attitude is celebrated "outward ceremony," Wayne Dwyer selling his 20,000 books and moving to Maui to follow the Tao, just what Oprah would like, an easy grasp of the profound. Blake says that the eternal body of man is the imagination and that to be a Christian is to be an artist, a poet/painter/musician/architect, and that that is the only preoccupation of the mind, gained over life and work, not in ease. Then we can know who the Christians are, not that art makes them so, it is just what the redeemed do.

Another way to demolish art and artist, Blake in particular, is to acknowledge his Christ, but claim him simply confused. Do not forget what they did to Orpheus, tore him limb from limb. So they call Blake's "a system so arcane, so embroiled in its own solipsistic mythology, that it is a resounding failure." "I will fit my small mind into his" should be the quest of these seekers of eternity in their dreams. Blake and his companions Milton and Hopkins lived it in the day. "Are you eternal?" You could ask the critics this, but they won't like it. George Richmond went walking with Blake, "feeling as if he were walking with the prophet Isaiah" (Davis, 154).

The smart people of the world want to ask, "was Jesus Christ a Christian?" But "all men are in eternity... though it appears Without, it is Within in your Imagination of which this World of Mortality is but a Shadow." So get on with your undressing. Should you never read to perceive another word of the flowering heart, know that this inwendigkeit is also the way peasant ancestors put into their art.

Blake forgets to be corrosive when he and his wife kneel and pray to the Holy Spirit for inspiration. (William Blake. A New Kind of Man. Michael Davis. 1977, 155). Imagine what critics do when he reincarnates Milton, as outside the rationalist experience as Milton's insistence that the Holy Ghost dictated Paradise Lost to him each night in entirety, which he told to his daughter the next day. So much of what passes for understanding by critics is amoral black and white. They are the very fundamentalists they themselves should flee. The artistic case has even more contradiction than the general human. To withstand the contradictions of Blake's opposite states without compromising the portrait he gives of himself as a Christian is often too much for critical funds. They must make him fit their idea of rationality and art, which they have been doing anyway everywhere, completely absurd.

Blake forgets to be corrosive when he and his wife kneel and pray to the Holy Spirit for inspiration. (William Blake. A New Kind of Man. Michael Davis. 1977, 155). Imagine what critics do when he reincarnates Milton, as outside the rationalist experience as Milton's insistence that the Holy Ghost dictated Paradise Lost to him each night in entirety, which he told to his daughter the next day. So much of what passes for understanding by critics is amoral black and white. They are the very fundamentalists they themselves should flee. The artistic case has even more contradiction than the general human. To withstand the contradictions of Blake's opposite states without compromising the portrait he gives of himself as a Christian is often too much for critical funds. They must make him fit their idea of rationality and art, which they have been doing anyway everywhere, completely absurd.Prophet

Talk about straining out a gnat to swallow a camel! A lot of Blake's biography derives from Tatham whose reports give Blake a pietistic tincture, reporting practices of prayer that indicate he is the opposite of a free thinker. The same Tatham burned and disposed much of Blake's literary remains. It did not meet his approval. Just so, critics continue to seek a Blake they can comfortably digest, but his rampant evangelicism is not to their taste. Blake is a prophet in the biblical vein. He says and does things as unprecedented as the biblical prophets.

A comparison for fraktur art and the way into the flowering heart in Blake stems not only from the art, but from the faith. As Stoudt says (Pennsylvania German Folk Art, 24) it is only when a species of disbelief took hold in the minds of the Pennsylvania faithful, what he calls liberalism, that their art failed. And that art under digital magnification continues to amaze, as we hope to show. So what of their faith? There are so many ex-fundamentalists with delicate sensibilities, but good upbringings, that many readers of Blake and Fraktur are impaired by their previous lives. Without naming names of our contemporary literary peers (at least not yet), this case affects Blake, who is celebrated for his "corrosive" art in the Marriage of Heaven and Hell, but only because critics pretend Blake is not a Christian.

What the Redeemed Do

What the Redeemed DoBlake is rather more than merely a Christian in name. He is one in his art, poetry and life, easiest to see in the art maybe, but in his poetry it is more dramatic. Critics gloss over these passages even as they explain them away, as Yeats does in his Introduction (Poems of William Blake), but there it still is, for example in Jerusalem where Blake invites, "I hope the reader will be with me wholly one in Jesus our Lord who is the God and Lord to whom the Ancients look'd and saw his day afar off with trembling & amazement." That alone goes further than allowed by the modern editor. Sorry Blake, "that isn't quite right for us." But Blake published himself and said what he would. Of course the subjects of his art are wholly biblical in every way, Job, notwithstanding the erosion that occurs from disinformation. If it sounds like this is a conspiracy to deny Blake his own faith, it is his critics who have denied their own.

In his personal life the reports of Blake and his wife are supernaturally scandalous, which information comes from Linnell. Of the application of fundamentalist attitudes to the poets however, witness the psychological dissection of Hopkins, who if he were what anthropologists used to call a "salvage" would have his own museum of reconstructions. Here he is a degenerate, there a fascist, any and all things where the good is remade into stereotypical evil that gets young peppery guys published. The essence of the fundamentalist attitude is celebrated "outward ceremony," Wayne Dwyer selling his 20,000 books and moving to Maui to follow the Tao, just what Oprah would like, an easy grasp of the profound. Blake says that the eternal body of man is the imagination and that to be a Christian is to be an artist, a poet/painter/musician/architect, and that that is the only preoccupation of the mind, gained over life and work, not in ease. Then we can know who the Christians are, not that art makes them so, it is just what the redeemed do.

In his personal life the reports of Blake and his wife are supernaturally scandalous, which information comes from Linnell. Of the application of fundamentalist attitudes to the poets however, witness the psychological dissection of Hopkins, who if he were what anthropologists used to call a "salvage" would have his own museum of reconstructions. Here he is a degenerate, there a fascist, any and all things where the good is remade into stereotypical evil that gets young peppery guys published. The essence of the fundamentalist attitude is celebrated "outward ceremony," Wayne Dwyer selling his 20,000 books and moving to Maui to follow the Tao, just what Oprah would like, an easy grasp of the profound. Blake says that the eternal body of man is the imagination and that to be a Christian is to be an artist, a poet/painter/musician/architect, and that that is the only preoccupation of the mind, gained over life and work, not in ease. Then we can know who the Christians are, not that art makes them so, it is just what the redeemed do.Another way to demolish art and artist, Blake in particular, is to acknowledge his Christ, but claim him simply confused. Do not forget what they did to Orpheus, tore him limb from limb. So they call Blake's "a system so arcane, so embroiled in its own solipsistic mythology, that it is a resounding failure." "I will fit my small mind into his" should be the quest of these seekers of eternity in their dreams. Blake and his companions Milton and Hopkins lived it in the day. "Are you eternal?" You could ask the critics this, but they won't like it. George Richmond went walking with Blake, "feeling as if he were walking with the prophet Isaiah" (Davis, 154).

The smart people of the world want to ask, "was Jesus Christ a Christian?" But "all men are in eternity... though it appears Without, it is Within in your Imagination of which this World of Mortality is but a Shadow." So get on with your undressing. Should you never read to perceive another word of the flowering heart, know that this inwendigkeit is also the way peasant ancestors put into their art.

4. The Most Profound Speakers of English

We are flat out of examples of the One Man who keeps cropping up in Blake's visions. When you wrap your arms around a man you are going to get a multitudinious contradiction. Adam Kadmon is not real! Billy Blake is going to be imperfect. Our secularists have gotten way too comfortable in shrinking a Christian down to a buffoon with the morals and prejudices of corruption. There is no need to compare him with an animal. The dog is noble. The wolf is noble. It is the man.

As we see Christians in art as w

riters, they are latitudinarians not Luthers. Blake says Luther kept whores. How modern of him. Christians are like Jonathan Swift. When his yahoo rains refuse down upon the narrator standing under a tree, that is what a christian would say in art. The broadness of a christian cannot be managed. Donne was a christian when he wrote the Songs and Sonnets. Later he says, "so they would read me throughout, and look upon me altogether...let all the world know all the sins of my youth, and of mine age too, and I would not doubt but God should receive more glory, and the world more benefit, than if I had never sinned ("On Prayer, Repentance, and the Mercy of God." Sermons. Ed by Edmund Fuller, 1964, 160).

riters, they are latitudinarians not Luthers. Blake says Luther kept whores. How modern of him. Christians are like Jonathan Swift. When his yahoo rains refuse down upon the narrator standing under a tree, that is what a christian would say in art. The broadness of a christian cannot be managed. Donne was a christian when he wrote the Songs and Sonnets. Later he says, "so they would read me throughout, and look upon me altogether...let all the world know all the sins of my youth, and of mine age too, and I would not doubt but God should receive more glory, and the world more benefit, than if I had never sinned ("On Prayer, Repentance, and the Mercy of God." Sermons. Ed by Edmund Fuller, 1964, 160).

So many of the most profound speakers of English own that language of faith. The only recourse of their enemy, another Christian idea, is to make it seem like there are hardly any Christian poets in English. There is hardly anything else. Wallace Stevens was a Christian! A forgiving bunch, they allow Dimmesdale back in the pulpit after a suitable time because "the gift of God is without repentence." Blake's specie of Christian, and remember that his works were burned by just those same specie, is still a page in Marriage where Palmer says "I think the whole page...would at once exclude the work from every drawing room table in England" (The Stranger From Paradise, 409).

Dimmesdale back in the pulpit after a suitable time because "the gift of God is without repentence." Blake's specie of Christian, and remember that his works were burned by just those same specie, is still a page in Marriage where Palmer says "I think the whole page...would at once exclude the work from every drawing room table in England" (The Stranger From Paradise, 409).

Who comes off worse in the pantheon of life, David, Solomon or Blake? It is hard to put asunder what their beliefs join together. It doesn't matter what outlandish thing Blake may have said or done; at root he belongs. Christians say, "by their fruits you will know them." Their chief supporting actor, Paul, began his career by making them betray themselves under threat of death. That was before, not after? There are all these escape clauses. Kill the body but don't mess the mind.

We Kneel Down and Pray

Linnell said he "found it hard to get the great mystic into their little thimble" (Stranger, 409). George Richmond, the youngest of the Ancients [a group who gathered respectfully around Blake at his end], an aspiring artist, in all naivete asked Blake one day what to do when: a) he wanted to know the will of God b) wanted to know whether to take care of his aged mother or fight in the French resistance or c) what to do when he was out of artistic gas: "To his astonishment, Blake turned to his wife suddenly and said: "It is just so with us, is it not, for weeks together, when the visions forsake us? What do we do then, Kate?" "We kneel down and pray, Mr. Blake" (Stranger, 403).

Dissenters speak the language of Enthusiasm, Bentley says, (365) citing Linnell, "The mind that rejects the true Prophet...generally follows the Beast also for the Beast & False-Prophet are always found together." Such notions of the prophetic are intimately biblical. They mean that "Blake claimed the possession of some powers only in a greater degree that all men possessed and which they undervalued in themselves & lost through love of sordid pursuits--pride, vanity, & the unrighteous mammon" (367). Yeats would come right out of his grave to get these powers. Think of the comfort that would give theosophists who in their work merely imitate the Christian! Try as he may Yeats cannot. We will visit him there soon. Stay tuned.Try as he would, to get "the power,"Yeats invented visions out of intellect. If you yourself see fleas in the spirit, as Blake, that is, originally perceive the unknown, be democratic and share the wealth with the poor!

Dissenters speak the language of Enthusiasm, Bentley says, (365) citing Linnell, "The mind that rejects the true Prophet...generally follows the Beast also for the Beast & False-Prophet are always found together." Such notions of the prophetic are intimately biblical. They mean that "Blake claimed the possession of some powers only in a greater degree that all men possessed and which they undervalued in themselves & lost through love of sordid pursuits--pride, vanity, & the unrighteous mammon" (367). Yeats would come right out of his grave to get these powers. Think of the comfort that would give theosophists who in their work merely imitate the Christian! Try as he may Yeats cannot. We will visit him there soon. Stay tuned.Try as he would, to get "the power,"Yeats invented visions out of intellect. If you yourself see fleas in the spirit, as Blake, that is, originally perceive the unknown, be democratic and share the wealth with the poor!

Infallibility

All men are equal, what! Tatham, burned the plates (Blake merely gouged them). This very tainted source, says when Blake thought he had the Seeing fixed "before his mind's Eye...that while he copied the vision (as he called it) upon his plate or canvas, he could not Err; & that error & defect could only arise from the departure or inaccurate delineation of this unsubstantial scene" (371). Blake's claim to infallibility in something nobody can confirm smacks of Enthusiasm. Enthusiasts must be taken for what they are. Bentley says "the testimony about Blake's madness among contemporaries who did not know him is close to unanimous" (379). Among those who knew him, at least prior to 1820, the case was only somewhat better.

Bentley gives an understanding that the grounds of his mad reputation were based on the observation that Blake's spiritual world was in form disconcertingly like the material outer world (380). Would we expect it to be different? Such "resemblances" (see Wallace Stevens' Necessary Angel, "The Figure of the Youth as a Virile Poet," 61) are necessary to recognize the form being seen. It is always the case in these philosophies, occult or other, that reflections of order occur for the purpose of recognition, that the Other is not hiding so much as hid by the viewer's blindness, as Linnell means about "sordid pursuits" that blind.

Draw Aside the Curtain

Evidence that after 1820 Blake became serene occurs in his Virgil woodcuts, his taking a glass of porter (393) and the conviviality of his circle, especially Edward Calvert, Samuel Palmer, George Richmond and Frederick Tatham (401). The woodcuts receive approval from all comers. Samuel Palmer, at the time said, "There is in all such a mystic and dreamy glimmer as penetrates and kindles the inmost soul, and gives complete and unreserved delight, unlike the gaudy daylight of this world. They are like all that wonderful artist's works the drawing aside of the fleshly curtain" (392). This flesh curtain is much at issue with Blake.

Never take what others say somebody said without compelling reason. That means what Varley or Crabb Robinson say Blake said is not much admissible as fact. Quote what Blake wrote. But Linnell is worthier. Is that because Varley is an astrologer and says Blake has Mercury square Mars which gives depth of mind! What about Blake's seances with the Visionary Heads? Blake, starved for company was adopted by a handful of young men who came to his house after 1820 and cultivated him. He told them he could see into the you know what, so Varley got him at a table and Blake drew heads like Edward I, etc. Then Blake drew the visionary head of a flea. That's the high art of spoof. Varley's too serious and is being mocked with a straight face. He says Blake said the flea was originally created large but had to be shrunk because it was too great a predator. It's a good thing Donne didn't hear about it! The sensationalisms of literature should be read as fiction. Shall Gulliver be turned into Hakluyt? He has, but look at the Colonials! Blake knew who Christians were, not that art made them, it is what the redeemed do. That was the inwendigkeit Anabaptists put in their art.

like Edward I, etc. Then Blake drew the visionary head of a flea. That's the high art of spoof. Varley's too serious and is being mocked with a straight face. He says Blake said the flea was originally created large but had to be shrunk because it was too great a predator. It's a good thing Donne didn't hear about it! The sensationalisms of literature should be read as fiction. Shall Gulliver be turned into Hakluyt? He has, but look at the Colonials! Blake knew who Christians were, not that art made them, it is what the redeemed do. That was the inwendigkeit Anabaptists put in their art.

If you are new to Blake go here.

Postscript

Dimmesdale back in the pulpit after a suitable time because "the gift of God is without repentence." Blake's specie of Christian, and remember that his works were burned by just those same specie, is still a page in Marriage where Palmer says "I think the whole page...would at once exclude the work from every drawing room table in England" (The Stranger From Paradise, 409).

Dimmesdale back in the pulpit after a suitable time because "the gift of God is without repentence." Blake's specie of Christian, and remember that his works were burned by just those same specie, is still a page in Marriage where Palmer says "I think the whole page...would at once exclude the work from every drawing room table in England" (The Stranger From Paradise, 409).Who comes off worse in the pantheon of life, David, Solomon or Blake? It is hard to put asunder what their beliefs join together. It doesn't matter what outlandish thing Blake may have said or done; at root he belongs. Christians say, "by their fruits you will know them." Their chief supporting actor, Paul, began his career by making them betray themselves under threat of death. That was before, not after? There are all these escape clauses. Kill the body but don't mess the mind.

We Kneel Down and Pray

Linnell said he "found it hard to get the great mystic into their little thimble" (Stranger, 409). George Richmond, the youngest of the Ancients [a group who gathered respectfully around Blake at his end], an aspiring artist, in all naivete asked Blake one day what to do when: a) he wanted to know the will of God b) wanted to know whether to take care of his aged mother or fight in the French resistance or c) what to do when he was out of artistic gas: "To his astonishment, Blake turned to his wife suddenly and said: "It is just so with us, is it not, for weeks together, when the visions forsake us? What do we do then, Kate?" "We kneel down and pray, Mr. Blake" (Stranger, 403).

Dissenters speak the language of Enthusiasm, Bentley says, (365) citing Linnell, "The mind that rejects the true Prophet...generally follows the Beast also for the Beast & False-Prophet are always found together." Such notions of the prophetic are intimately biblical. They mean that "Blake claimed the possession of some powers only in a greater degree that all men possessed and which they undervalued in themselves & lost through love of sordid pursuits--pride, vanity, & the unrighteous mammon" (367). Yeats would come right out of his grave to get these powers. Think of the comfort that would give theosophists who in their work merely imitate the Christian! Try as he may Yeats cannot. We will visit him there soon. Stay tuned.Try as he would, to get "the power,"Yeats invented visions out of intellect. If you yourself see fleas in the spirit, as Blake, that is, originally perceive the unknown, be democratic and share the wealth with the poor!

Dissenters speak the language of Enthusiasm, Bentley says, (365) citing Linnell, "The mind that rejects the true Prophet...generally follows the Beast also for the Beast & False-Prophet are always found together." Such notions of the prophetic are intimately biblical. They mean that "Blake claimed the possession of some powers only in a greater degree that all men possessed and which they undervalued in themselves & lost through love of sordid pursuits--pride, vanity, & the unrighteous mammon" (367). Yeats would come right out of his grave to get these powers. Think of the comfort that would give theosophists who in their work merely imitate the Christian! Try as he may Yeats cannot. We will visit him there soon. Stay tuned.Try as he would, to get "the power,"Yeats invented visions out of intellect. If you yourself see fleas in the spirit, as Blake, that is, originally perceive the unknown, be democratic and share the wealth with the poor!Infallibility

All men are equal, what! Tatham, burned the plates (Blake merely gouged them). This very tainted source, says when Blake thought he had the Seeing fixed "before his mind's Eye...that while he copied the vision (as he called it) upon his plate or canvas, he could not Err; & that error & defect could only arise from the departure or inaccurate delineation of this unsubstantial scene" (371). Blake's claim to infallibility in something nobody can confirm smacks of Enthusiasm. Enthusiasts must be taken for what they are. Bentley says "the testimony about Blake's madness among contemporaries who did not know him is close to unanimous" (379). Among those who knew him, at least prior to 1820, the case was only somewhat better.

Bentley gives an understanding that the grounds of his mad reputation were based on the observation that Blake's spiritual world was in form disconcertingly like the material outer world (380). Would we expect it to be different? Such "resemblances" (see Wallace Stevens' Necessary Angel, "The Figure of the Youth as a Virile Poet," 61) are necessary to recognize the form being seen. It is always the case in these philosophies, occult or other, that reflections of order occur for the purpose of recognition, that the Other is not hiding so much as hid by the viewer's blindness, as Linnell means about "sordid pursuits" that blind.

Draw Aside the Curtain

Evidence that after 1820 Blake became serene occurs in his Virgil woodcuts, his taking a glass of porter (393) and the conviviality of his circle, especially Edward Calvert, Samuel Palmer, George Richmond and Frederick Tatham (401). The woodcuts receive approval from all comers. Samuel Palmer, at the time said, "There is in all such a mystic and dreamy glimmer as penetrates and kindles the inmost soul, and gives complete and unreserved delight, unlike the gaudy daylight of this world. They are like all that wonderful artist's works the drawing aside of the fleshly curtain" (392). This flesh curtain is much at issue with Blake.

Never take what others say somebody said without compelling reason. That means what Varley or Crabb Robinson say Blake said is not much admissible as fact. Quote what Blake wrote. But Linnell is worthier. Is that because Varley is an astrologer and says Blake has Mercury square Mars which gives depth of mind! What about Blake's seances with the Visionary Heads? Blake, starved for company was adopted by a handful of young men who came to his house after 1820 and cultivated him. He told them he could see into the you know what, so Varley got him at a table and Blake drew heads

like Edward I, etc. Then Blake drew the visionary head of a flea. That's the high art of spoof. Varley's too serious and is being mocked with a straight face. He says Blake said the flea was originally created large but had to be shrunk because it was too great a predator. It's a good thing Donne didn't hear about it! The sensationalisms of literature should be read as fiction. Shall Gulliver be turned into Hakluyt? He has, but look at the Colonials! Blake knew who Christians were, not that art made them, it is what the redeemed do. That was the inwendigkeit Anabaptists put in their art.

like Edward I, etc. Then Blake drew the visionary head of a flea. That's the high art of spoof. Varley's too serious and is being mocked with a straight face. He says Blake said the flea was originally created large but had to be shrunk because it was too great a predator. It's a good thing Donne didn't hear about it! The sensationalisms of literature should be read as fiction. Shall Gulliver be turned into Hakluyt? He has, but look at the Colonials! Blake knew who Christians were, not that art made them, it is what the redeemed do. That was the inwendigkeit Anabaptists put in their art.If you are new to Blake go here.

Postscript

"Nearly all of us have felt, at least in childhood, that if we imagine that a thing is so, it therefore either is so or can be made to become so. All of us have to learn that this almost never happens, or happens only in very limited ways; but the visionary, like the child, continues to believe that it always ought to happen. We are so possessed with the idea of the duty of acceptance that we are inclined to forget our mental birthright, and prudent and sensible people encourage us in this. This is why Blake is so full of aphorisms like "If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise." Such wisdom is based on the fact that imagination creates reality, and as desire is a part of imagination, the world we desire is more real than the world we passively accept" (Northrop Frye, Fearful Symmetry, 27).

I was studying Blake and made a living off his Tyger. It produced four paychecks. Thinking to calve a Blake comic, I got copies of the slides of Jerusalem before cellphones, but the cost of production outran. They are reproduced here in black and white. Imagine Blake street-bound in newsprint of lurid colors! Ignorance is a kind of grace and Enthusiasm its naivete.